Fight or Flight Response: Definition, Response, Examples, & How to Calm?

The fight or flight response, called the acute stress response, is our body’s natural reaction to perceived danger. It’s a survival mechanism designed to help us confront or escape threats.

When faced with stress—whether a car breaks down in front of you or a looming deadline—your body activates this response by releasing hormones like adrenaline and cortisol.

These changes prepare you to react quickly, increasing your heart rate, sharpening your focus, and supplying extra energy.

Understanding the fight or flight response is important because it doesn’t just affect us in moments of crisis.

While it can be life-saving in real emergencies, constant activation due to everyday stress can damage physical and mental health.

Issues like chronic anxiety, high blood pressure, and difficulty sleeping often stem from an overactive stress response. Recognizing how your body reacts to stress can help you manage it more effectively.

Physiologist Walter Cannon first described the fight or flight response in the early 1900s. His groundbreaking work highlighted how the body’s systems respond to threats, laying the foundation for modern stress research.

By exploring the origins, examples, and ways to calm this response, we can better understand how to navigate stress in healthier, more balanced ways.

The Three Stages of the Fight or Flight Response

The fight or flight response unfolds in three key stages: the alarm stage, the resistance stage, and the exhaustion stage.

These stages represent the body’s reaction to stress, from the initial trigger to its eventual resolution or prolonged effects.

Understanding these stages can help us recognize how stress affects our body and mind, enabling better management of its impact. Below is a detailed breakdown of each stage.

1. Alarm Stage

The alarm stage is the body’s immediate reaction to a perceived threat. The central nervous system activates when danger is detected, releasing stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol.

These hormones trigger a series of physical changes, such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and heightened senses, all designed to prepare the body for action.

Blood flow is directed to essential muscles, pupils dilate to improve vision, and digestion slows down to conserve energy. This stage is crucial for survival, equipping the body to respond quickly to emergencies.

2. Resistance Stage

Once the initial shock of the alarm stage passes, the resistance stage begins. During this phase, the body works to return to its baseline state, known as homeostasis. Stress hormone levels gradually decrease, and normal bodily functions resume.

However, the resistance stage may be prolonged if the stressor persists or the body cannot fully recover.

This can result in a state of heightened alertness, where the body is not fully at rest but still attempting to manage the stress.

3. Exhaustion Stage

If stress continues for an extended period or occurs repeatedly without resolution, the body enters the exhaustion stage.

Prolonged activation of the fight or flight response can consume physical and emotional resources, leading to burnout, fatigue, or other health issues, such as weakened immunity and high blood pressure.

The exhaustion stage highlights the importance of managing stress effectively, as chronic stress can have long-term consequences on overall well-being.

Recognizing these stages helps identify when stress is becoming unmanageable and take proactive steps to reduce its effects.

Origin of the Fight or Flight Response

The fight or flight response has deep evolutionary roots, serving as a vital mechanism for survival in ancient environments.

When early humans encountered predators or life-threatening situations, this acute stress response enabled them to confront the danger (fight) or flee to safety (flight).

It is a physiological adaptation that ensures survival by preparing the body for immediate action. This mechanism wasn’t just limited to humans; it is seen across many species, reflecting its fundamental role in evolution.

Over time, researchers have studied and expanded upon this concept. Walter Cannon first described the fight or flight response in the early 20th century, highlighting its role in the body’s stress reaction.

Later, Hans Selye built on this work with his theory of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), which outlines three stages of stress: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion.

Selye’s work emphasized that the body’s response to stress is not limited to acute threats but also involves long-term effects, linking the fight or flight response to broader stress management concepts.

In modern life, the fight or flight response has transitioned from responding to physical dangers to dealing with psychological stressors, such as work pressures, financial worries, or social conflicts.

While the response remains the same—the triggers are less about survival and more about dealing with complex social and emotional challenges.

Understanding its origins and evolution helps us appreciate the fight or flight response as a protective mechanism and a potential source of chronic stress. This knowledge is crucial for managing stress effectively and maintaining overall well-being.

What Happens to the Body during the Fight or Flight Response?

The fight or flight response triggers a series of physiological changes in the body, designed to prepare for immediate action when faced with a threat.

The sympathetic nervous system controls this automatic reaction, which involves a surge of stress hormones and noticeable physical and emotional effects.

These changes work together to heighten awareness, boost energy, and focus all resources on survival. Below, we break down what happens in detail.

Hormonal Activation

The fight or flight response begins with the activation of the hypothalamus, a region in the brain that signals the adrenal glands to release stress hormones like adrenaline (epinephrine), noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and cortisol.

- Adrenaline and Noradrenaline: These hormones increase heart rate, breathing rate, and blood flow to major muscles, priming the body for action.

- Cortisol: Known as the stress hormone, cortisol maintains the body’s heightened readiness, ensuring energy is available by increasing glucose levels in the blood.

Simultaneously, the sympathetic nervous system takes control, triggering widespread changes that enhance the body’s ability to react quickly and effectively.

Physical Responses

Once hormones are released, they induce several physical responses aimed at optimizing the body for action:

- Increased Heart Rate and Respiration: The heart pumps faster to deliver oxygen and nutrients to muscles, while breathing accelerates to increase oxygen intake.

- Blood Flow Changes: Blood is redirected from non-essential areas, like the skin and digestive system, to the muscles and brain, ensuring they have the energy and oxygen needed for rapid movement or decision-making. This can cause pale skin or a “cold” sensation.

- Pupil Dilation: The eyes become more light-sensitive, improving vision to detect potential threats.

- Muscle Tension: Muscles tighten, preparing the body for immediate action. While helpful in emergencies, prolonged muscle tension can lead to discomfort or pain.

While life-saving is in real danger, these responses can become problematic when triggered by everyday stressors.

Understanding these changes helps manage stress more effectively and mitigate the adverse effects of an overactive fight or flight response.

Impact of the Fight or Flight Response

The fight or flight response has both positive and negative impacts, depending on the situation and how frequently it is activated.

In the short term, this response can be a powerful survival tool, sharpening focus and physical ability during critical moments. However, when it becomes overactive due to chronic stress or false alarms, it can lead to physical and mental health challenges.

By understanding its dual impact, we can appreciate its role in survival while addressing its potential downsides.

Benefits

Here are the main benefits of fight-and-flight response:

- Enhanced Performance Under Pressure: The fight or flight response can boost performance in situations requiring quick thinking or physical action. Whether in a high-stakes work presentation, a competitive sports event, or a survival scenario, this response enhances physical and mental capabilities to meet challenges.

- Increased Focus and Quick Response to Danger: The surge of adrenaline heightens focus, allowing individuals to process information rapidly and make split-second decisions. This clarity can be critical in emergencies, such as avoiding a car accident or escaping a dangerous situation.

- Protective Instincts During Emotional Stress: Beyond physical dangers, the response can help protect against emotional stress, such as defending oneself in a verbal conflict or acting decisively in emotionally charged situations.

Drawbacks

Here are the significant drawbacks associated with fight-and-flight response:

- False Triggers from Perceived Threats: In modern life, many triggers are psychological rather than physical, such as anger, phobias, public speaking anxiety, or conflicts at work. These false alarms unnecessarily activate the fight or flight response, creating discomfort without resolving the situation.

- Chronic Stress Leading to Health Issues: Frequent activation of the fight or flight response can take a toll on the body. Chronic stress is linked to conditions like heart disease, migraines, high blood pressure, and weakened immunity. Over time, the body becomes less efficient at managing stress, leading to burnout or fatigue.

- Link to Mental Health Conditions: An overactive response is associated with mental health conditions like anxiety disorders, where perceived threats continually trigger the stress response. This can result in excessive worry, panic attacks, or feeling overwhelmed.

While the fight or flight response is an essential survival mechanism, understanding and managing it is crucial to maintaining physical and mental well-being in today’s stress-filled world.

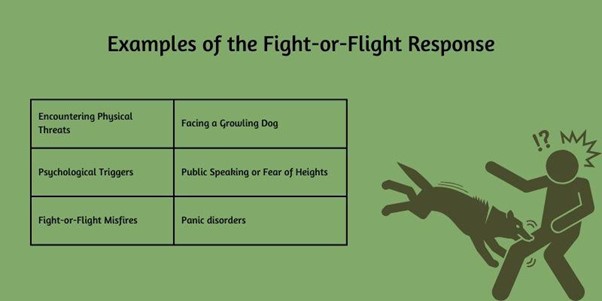

Examples of the Fight or Flight Response

Both physical and psychological threats can trigger the fight or flight response. While it evolved to help humans react to immediate danger, in today’s world, it often activates in situations that don’t require such intense responses.

Here are some examples of how this stress response manifests in real-life situations.

Encountering Physical Threats: Facing a Growling Dog

When confronted with a physical threat, such as a growling dog or a potentially dangerous animal, the fight or flight response is triggered immediately.

The body releases adrenaline and other stress hormones, preparing the person to either fight the dog to protect themselves or flee to safety.

In this case, the body reacts with heightened senses, increased heart rate, and a surge of energy, enabling the individual to act quickly. This response is crucial for survival, as it prepares the body to defend itself or escape harm.

Psychological Triggers: Public Speaking or Fear of Heights

The fight or flight response isn’t limited to physical threats; psychological stressors can also trigger it.

For example, someone might experience intense anxiety and a surge of adrenaline before speaking in public, even if there is no actual physical danger.

Similarly, people who fear heights may experience the same physiological reactions when looking at a tall building or standing near an edge.

In these cases, the body reacts as though facing an immediate threat, even though the danger is perceived rather than real. Though appropriate in emergencies, the heightened sense of urgency and readiness to act can be overwhelming in non-life-threatening situations.

Panic Disorder Linked to Fight or Flight Misfires

Panic disorder is an example of when the fight or flight response misfires. Individuals with this disorder experience sudden, intense feelings of fear or dread, often without an obvious trigger.

The body’s fight or flight system activates for no reason, causing symptoms such as a racing heart, difficulty breathing, and dizziness.

This heightened stress response can lead to a cycle of panic attacks, where the individual becomes increasingly afraid of the physical sensations associated with the response, triggering more panic episodes.

Managing panic disorder often involves learning how to regulate the body’s reaction to stress so it doesn’t spiral out of control.

These examples illustrate how the fight or flight response, while essential for survival in some situations, can also become overactive or misdirected in modern life.

Recognizing these triggers and understanding the body’s reaction can help individuals manage their stress response more effectively.

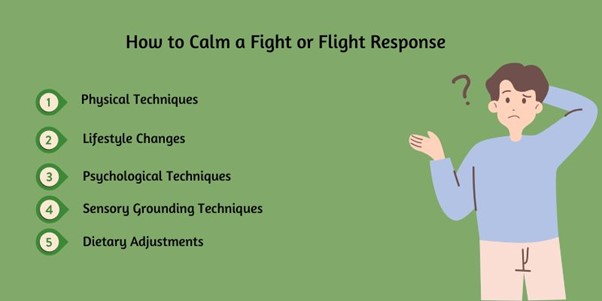

How to Calm a Fight or Flight Response

Managing the fight or flight response is essential for reducing the negative effects of chronic stress and maintaining both physical and mental well-being.

Although this response is natural and designed for survival, prolonged activation due to constant stress or anxiety can lead to health issues like heart disease, depression, and burnout.

Fortunately, several techniques can help calm the body’s fight or flight response and restore balance. Below are some methods to effectively manage and reduce the response.

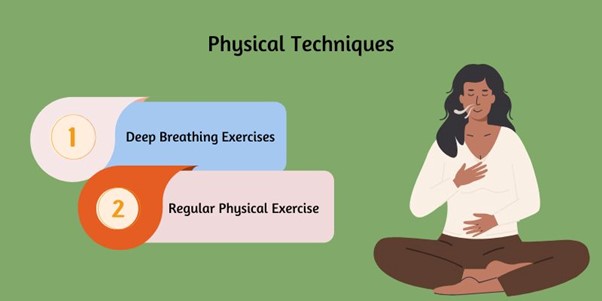

1. Physical Techniques

- Deep Breathing Exercises: One of the quickest and most effective ways to calm the fight or flight response is through controlled breathing. Deep breathing, particularly diaphragmatic breathing (where you breathe deeply into your diaphragm), helps to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which counteracts the stress response. Slowly inhaling and exhaling can reduce your heart rate and lower cortisol levels, signaling to your body that the danger has passed.

- Regular Physical Exercise: Exercise is a powerful way to release built-up tension and manage stress. Physical activity helps regulate hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, promoting the release of endorphins (natural mood enhancers). Regular exercise, such as walking, jogging, or yoga, can reduce the frequency and intensity of the fight or flight response over time, allowing the body to return to calm after stressful events.

2. Lifestyle Changes

- Prioritizing Sleep and Rest: Chronic stress can make it difficult to relax and sleep, which only amplifies the fight or flight response. Prioritizing restful sleep helps the body restore itself and regulate stress hormones. Sleep improves the functioning of the autonomic nervous system, helping the body to switch from the high-alert state of fight or flight to a more balanced, relaxed state.

- Building a Strong Support Network: Having a solid network of friends, family, or colleagues to confide in can significantly reduce stress. Social support allows individuals to express their worries and feel heard, which helps release emotional tension and reduce the need for a fight or flight response. Building a strong, positive social network can act as a buffer against daily stressors.

3. Psychological Techniques

- Relaxation Exercises like Meditation and Mindfulness: Meditation and mindfulness are powerful tools for calming the mind and body. These techniques focus on being present in the moment and observing your thoughts without judgment. Regular practice can help break the cycle of stress-induced thinking, reduce anxiety, and regulate the fight or flight response. Meditation can also enhance emotional resilience, allowing you to handle challenges without triggering a stress reaction.

- Cognitive Strategies for Reframing Stressors: Cognitive strategies involve challenging and changing how we perceive stressors. Instead of viewing a situation as a threat, reframing it as a manageable challenge can reduce the body’s reaction. Techniques like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can teach individuals to recognize irrational thoughts and replace them with more realistic, calming perspectives, thus reducing the intensity of the fight or flight response.

4. Sensory Grounding Techniques

Grounding techniques can help you refocus your mind and calm the body during a fight or flight reaction.

These techniques involve using your senses to bring your attention back to the present moment.

For example, focusing on the sensation of your feet on the ground, the sounds around you, or the texture of an object can help interrupt the stress cycle and bring your nervous system back to a balanced state.

Sensory grounding helps reorient the mind away from stress and toward safety.

5. Dietary Adjustments

What you eat can significantly affect how your body responds to stress. Certain foods and beverages can either heighten or soothe the fight or flight response.

For example, reducing caffeine intake can prevent overstimulation of the nervous system, while foods rich in magnesium (like leafy greens and nuts) can help calm the body.

Additionally, eating balanced meals that stabilize blood sugar levels can prevent mood swings and irritability, which can trigger the fight or flight response. Maintaining a nutritious diet supports overall health and helps manage stress.

By combining these physical, psychological, and lifestyle strategies, individuals can significantly reduce the frequency and intensity of the fight or flight response.

Consistent practice of these techniques can lead to better stress management and a more balanced, healthy response to everyday challenges.

Conclusion

The fight or flight response is a crucial survival mechanism that prepares the body to react swiftly to danger.

This response helps us respond to immediate threats by triggering physical and psychological changes that enable us to fight or flee.

In today’s world, however, this response is often triggered by less immediate but still stress-inducing situations such as work pressures or personal challenges.

While the fight or flight response can be beneficial in acute stress scenarios, chronic activation can lead to negative effects on both physical and mental health.

Prolonged stress can contribute to issues such as anxiety, heart disease, and burnout. Therefore, finding a balance is key.

We can better manage this natural response by implementing healthy coping techniques, such as deep breathing, regular exercise, relaxation exercises, and cognitive reframing.

It’s important to recognize when the fight or flight response is being activated unnecessarily and to take steps to calm the body and mind.

Exploring various stress management methods can reduce the impact of this stress response and improve overall well-being.

Responses